Fe Cation Charge

- Common Cations and Anions Name Formula Charge Name Formula Charge Name Formula Charge aluminum Al 3+ +3 magnesium Mg 2+ +2 carbonate CO 3 2– –2 ammonium NH 4 + +1 manganese (II) Mn 2+ +2 chlorate ClO.

- The BVS results in Fig. 4c show that both Fe1 and Fe2 sites have mixed Fe 2+ /Fe 3+ charge states at 75–400 K, but charge ordering is evident at 5 K with Fe1 and Fe2 respectively tending to Fe 3+ and Fe 2+ states. The effect of Jahn Teller distortion (QJT) is also calculated for both Fe sites.

- When naming ionic compounds which contain metal ions capable of forming more than one kind of cation, the Roman numeral after the metal's name indicates the charge. Therefore, the iron cation in iron(II) chloride has a charge of 2^+, and the charge on the iron cation in iron(III) chloride has a charge of 3^+'.

- Ferrous cation Fe-57 Fe+2 CID 71587104 - structure, chemical names, physical and chemical properties, classification, patents, literature, biological activities.

Predicted data is generated using the US Environmental Protection Agency’s EPISuite™. Log Octanol-Water Partition Coef (SRC): Log Kow (KOWWIN v1.67 estimate) = -0.77 Boiling Pt, Melting Pt, Vapor Pressure Estimations (MPBPWIN v1.42): Boiling Pt (deg C): 482.98 (Adapted Stein & Brown method) Melting Pt (deg C): 188.60 (Mean or Weighted MP) VP(mm Hg,25 deg C): 4.24E-009 (Modified Grain.

In chemistry, iron(III) refers to the elementiron in its +3 oxidation state. In ionic compounds (salts), such an atom may occur as a separate cation (positive ion) denoted by Fe3+.

The adjective ferric or the prefix ferri- is often used to specify such compounds — as in 'ferric chloride' for iron(III) chloride, FeCl

3. The adjective 'ferrous' is used instead for iron(II) salts, containing the cation Fe2+. The word ferric is derived from the Latin word ferrum for iron.

Fe Cation Charge

Iron(III) metal centres also occur in coordination complexes, such as in the anionferrioxalate, [Fe(C

2O

4)

3]3−, where three bidentateoxalate ions surrounding the metal centre; or, in organometallic compounds, such as the ferrocenium cation [Fe(C

2H

5)

2]+, where two cyclopentadienyl anions are bound to the FeIII centre.

Iron is almost always encountered in the oxidation states 0 (as in the metal), +2, or +3. Iron(III) is usually the most stable form in air, as illustrated by the pervasiveness of rust, an insoluble iron(III)-containing material.

Iron(III) and life[edit]

All known forms of life require iron. Many proteins in living beings contain bound iron(III) ions; those are an important subclass of the metalloproteins. Examples include oxyhemoglobin, ferredoxin, and the cytochromes.

Almost all living organisms, from bacteria to humans, store iron as microscopic crystals (3 to 8 nm in diameter) of iron(III) oxide hydroxide, inside a shell of the protein ferritin, from which it can be recovered as needed. [1]

Insufficient iron in the human diet causes anemia. Animals and humans can obtain the necessary iron from foods that contain it in assimilable form, such as meat. Other organisms must obtain their iron from the environment. However, iron tends to form highly insoluble iron(III) oxides/hydroxides in aerobic (oxygenated) environment, especially in calcareous soils. Bacteria and grasses can thrive in such environments by secreting compounds called siderophores that form soluble complexes with iron(III), that can be reabsorbed into the cell. (The other plants instead encourage the growth around their roots of certain bacteria that reduce iron(III) to the more soluble iron(II).)[2]

The formation of insoluble iron(III) compounds is also responsible for the low levels of iron in seawater, which is often the limiting factor for the growth of the microscopic plants (phytoplankton) that are the basis of the marine food web.[3]

The insolubility of iron(III) compounds can be exploited to remedy eutrophication (excessive growth of algae) in lakes contaminated by excess soluble phosphates from farm runoff. Iron(III) combines with the phosphates to form insoluble iron(III) phosphate, thus reducing the bioavailability of phosphorus — another essential element that may also be a limiting nutrient.[citation needed]

Chemistry of iron(III)[edit]

Some iron(III) salts, like the chlorideFeCl

3, sulfateFe

2(SO

4)

3, and nitrateFe(NO

3)

3 are soluble in water. However, other salts like oxideFe

2O

3 (hematite) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxideFeO(OH) are extremely insoluble, at least at neutral pH, due to their polymeric structure. Therefore, those soluble iron(III) salts tend to hydrolyze when dissolved in pure water, producing iron(III) hydroxideFe(OH)

3 that immediately converts to polymeric oxide-hydroxide via the process called olation and precipitates out of the solution. That reaction liberates hydrogen ions H+ to the solution, lowering the pH, until an equilibrium is reached.[4]

- Fe3+ + 2 H

2O ⇌ FeO(OH) + 3 H+

As a result, concentrated solutions of iron(III) salts are quite acidic. The easy reduction of iron(III) to iron(II) lets iron(III) salts function also as oxidizers. Iron(III) chloride solutions are used to etch copper-coated plastic sheets in the production of printed circuit boards.[citation needed]

This behavior of iron(III) salts contrasts with salts of cations whose hydroxides are more soluble, like sodium chlorideNaCl (table salt), that dissolve in water without noticeable hydrolysis and without lowering the pH.[4]

Rust is a mixture of iron(III) oxide and oxide-hydroxide that usually forms when iron metal is exposed to humid air. Unlike the passivating oxide layers that are formed by other metals, like chromium and aluminum, rust flakes off, because it is bulkier than the metal that formed it. Therefore, unprotected iron objects will in time be completely turned into rust

Complexes[edit]

Iron(III) is a d5 center, meaning that the metal has five 'valence' electrons in the 3d orbital shell. These partially filled or unfilled d-orbitals can accept a large variety of ligands to form coordination complexes. The number and type of ligands is described by ligand field theory. Usually ferric ions are surrounded by six ligands arranged in octahedron; but sometimes three and sometimes as many as seven ligands are observed.

Various chelating compounds cause iron oxide-hydroxide (like rust) to dissolve even at neutral pH, by forming soluble complexes with the iron(III) ion that are more stable than it. These ligands include EDTA, which is often used to dissolve iron deposits or added to fertilizers to make iron in the soil available to plants. Citrate also solubilizes ferric ion at neutral pH, although its complexes are less stable than those of EDTA.

Magnetism[edit]

The magnetism of ferric compounds is mainly determined by the five d-electrons, and the ligands that connect to those orbitals.

Analysis[edit]

In qualitative inorganic analysis, the presence of ferric ion can be detected by the formation of its thiocyanate complex. Addition of thiocyanate salts to the solution gives the intensely red 1:1 complex.[5][6] The reaction is a classic school experiment to demonstrate Le Chatelier's principle:

- [Fe(H

2O)

6]3+ + SCN−

⇌ [Fe(SCN)(H

2O)

5]2+ + H

2O

See also[edit]

- Ferric chloride (Iron(III) chloride)

- Ferric oxide (Iron(III) oxide)

- Ferric fluoride (Iron(III) fluoride)

References[edit]

- ^Berg, Jeremy Mark; Lippard, Stephen J. (1994). Principles of bioinorganic chemistry. Sausalito, Calif: University Science Books. ISBN0-935702-73-3.

- ^H. Marschner and V. Römheld (1994): 'Strategies of plants for acquisition of iron'. Plant and Soil, volume 165, issue 2, pages 261–274. doi:10.1007/BF00008069

- ^Boyd PW, Watson AJ, Law CS, et al. (October 2000). 'A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization'. Nature. 407 (6805): 695–702. Bibcode:2000Natur.407..695B. doi:10.1038/35037500. PMID11048709.

- ^ abEarnshaw, A.; Greenwood, N. N. (1997). Chemistry of the elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN0-7506-3365-4.

- ^Lewin, Seymour A.; Wagner, Roselin Seider (1953). 'The nature of iron(III) thiocyanate in solution'. Journal of Chemical Education. 30 (9): 445. Bibcode:1953JChEd..30..445L. doi:10.1021/ed030p445.

- ^Bent, H. E.; French, C. L. (1941). 'The Structure of Ferric Thiocyanate and its Dissociation in Aqueous Solution'. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 63 (2): 568–572. doi:10.1021/ja01847a059.

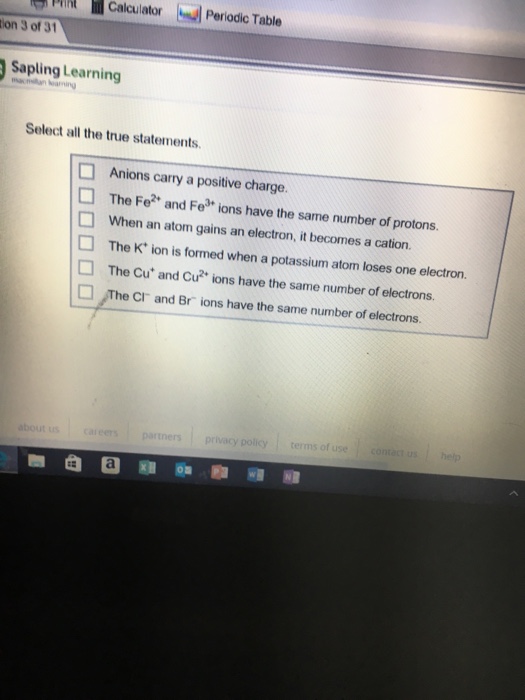

Learning Objectives

- Know how ions form.

- Learn the characteristic charges that ions have.

- Construct a proper formula for an ionic compound.

- Generate a proper name for an ionic compound.

So far, we have discussed elements and compounds that are electrically neutral. They have the same number of electrons as protons, so the negative charges of the electrons is balanced by the positive charges of the protons. However, this is not always the case. Electrons can move from one atom to another; when they do, species with overall electric charges are formed. Such species are called ions. Species with overall positive charges are termed cations, while species with overall negative charges are called anions. Remember that ions are formed only when electrons move from one atom to another; a proton never moves from one atom to another. Compounds formed from positive and negative ions are ionic compounds.

Fe Cation Charge Formula

Individual atoms can gain or lose electrons. When they do, they become monatomic ions. When atoms gain or lose electrons, they usually gain or lose a characteristic number of electrons and so take on a characteristic overall charge. Figure (PageIndex{1}) shows some common ions in terms of how many electrons they lose (making cations) or gain (making anions), as well as their positions on the periodic table. There are several things to notice about the ions in Figure (PageIndex{1}). First, each element that forms cations is a metal, except for one (hydrogen), while each element that forms anions is a nonmetal. This is actually one of the chemical properties of metals and nonmetals: metals tend to form cations, while nonmetals tend to form anions. Second, elements that live in the first two columns and the last three columns of the period table show a defininte trend in charges. Every element in the first column forms a cation with charge 1+. Every element in the second column forms a cation with charge 2+. Elements in the third to last column almost all form an anion with a 2- charge and elements living in the second to last column almost all form anions with a 1- charge. The elements at the end of the periodic table do not form ions. We'll learn more about why this is the case in future chapters but for the time being if you can learn this trend it's fairly easy to determine the charge on most of the elements we see. Finally, most atoms form ions of a single characteristic charge. When sodium atoms form ions, they always form a 1+ charge, never a 2+ or 3+ or even 1− charge. Thus, if you commit the information in Figure (PageIndex{1}) to memory, you will always know what charges most atoms form.

Figure (PageIndex{1}): Groups on the periodic table and the charges on their ions, By Homme en Noir - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/inde...curid=66743988

While Figure (PageIndex{1}) is helpful in determining the charge on a large number of our cations and anions it's hardly complete. A more complete table of ions and their charges can be found at Monotomic Ions of Various Charges. Examination of the table in the link given shows that there are some exceptions to the previous point. A few elements, all metals, can form more than one possible charge. For example, iron (Fe) atoms can form 2+ cations or 3+ cations. Cobalt (Co) is another element that can form more than one possible charged ion (2+ and 3+), while lead (Pb) can form 2+ or 4+ cations. Unfortunately, there is little understanding which two charges a metal atom may take, so it is best to just memorize the possible charges a particular element can have.

Note the convention for indicating an ion. The magnitude of the charge is listed as a right superscript next to the symbol of the element. If the charge is a single positive or negative one, the number 1 is not written; if the magnitude of the charge is greater than 1, then the number is written before the + or − sign. An element symbol without a charge written next to it is assumed to be the uncharged atom.

Naming ions

Naming an ion is straightforward. For a cation, simply use the name of the element and add the word ion (or if you want to be more specific, add cation) after the element’s name. So Na+ is the sodium ion; Ca2+ is the calcium ion. If the element has more than one possible charge, the value of the charge comes after the element name and before the word ion. Thus, Fe2+ is the iron two ion, while Fe3+ is the iron three ion. In print, we use roman numerals in parentheses to represent the charge on the ion, so these two iron ions would be represented as the iron(II) cation and the iron(III) cation, respectively.

For a monatomic anion, use the stem of the element name and append the suffix -ide to it, and then add ion. This is similar to how we named molecular compounds. Thus, Cl− is the chloride ion, and N3− is the nitride ion.

Example (PageIndex{1}):

Name each species.

- O2−

- Co

- Co2+

Solution

- This species has a 2− charge on it, so it is an anion. Anions are named using the stem of the element name with the suffix -ide added. This is the oxide anion.

- Because this species has no charge, it is an atom in its elemental form. This is cobalt.

- In this case, there is a 2+ charge on the atom, so it is a cation. We note from Table 3.4.1 that cobalt cations can have two possible charges, so the name of the ion must specify which charge the ion has. This is the cobalt(II) cation.

Exercise (PageIndex{1})

Name each species.

- P3−

- Sr2+

Answers

- the phosphide anion

- the strontium cation

Ionic Formulas

Chemical formulas for ionic compounds are called ionic formulas. A proper ionic formula has a cation and an anion in it; an ionic compound is never formed between two cations only or two anions only. If you've ever tried to force two refrigerator magnets together you'll remember that there was one side of each magnet that clicked together and there was one side of each magnet that pushed against the other. One side of each of our magnets is positive and one side of each of our magnets is negative. When the magnets push away from each other we're trying to force two like charges together. Ions behave the same way on the atomic scale. Two ions with the same charge will push away from each other. Two ions with opposite charges will be attracted to each other as being close to one another allows them to cancel out the additional charge they are carrying. A Ca2+ cation has twice as much charge as a Cl- anion, so it will be able to attract and cancel out the charge on two Cl- anions.

The key to writing proper ionic formulas is simple: the total positive charge must balance the total negative charge. Because the charges on the ions are characteristic, sometimes we have to have more than one of a cation or an anion to balance the overall positive and negative charges. It is conventional to use the lowest ratio of ions that are needed to balance the charges.

For example, consider the ionic compound between Na+ and Cl−. Each ion has a single charge, one positive and one negative, so we need only one ion of each to balance the overall charge. When writing the ionic formula, we follow two additional conventions: (1) write the formula for the cation first and the formula for the anion next, but (2) do not write the charges on the ions. Thus, for the compound between Na+ and Cl−, we have the ionic formula NaCl (Figure (PageIndex{1})). The formula Na2Cl2 also has balanced charges, but the convention is to use the lowest ratio of ions, which would be one of each. (Remember from our conventions for writing formulas that we don’t write a 1 subscript if there is only one atom of a particular element present.) For the ionic compound between magnesium cations (Mg2+) and oxide anions (O2−), again we need only one of each ion to balance the charges. By convention, the formula is MgO.

Figure (PageIndex{1}): NaCl = Table Salt © Thinkstock The ionic compound NaCl is very common.

For the ionic compound between Mg2+ ions and Cl− ions, we now consider the fact that the charges have different magnitudes, 2+ on the magnesium ion and 1− on the chloride ion. To balance the charges with the lowest number of ions possible, we need to have two chloride ions to balance the charge on the one magnesium ion. Rather than write the formula MgClCl, we combine the two chloride ions and write it with a 2 subscript: MgCl2.

What is the formula MgCl2 telling us? There are two chloride ions in the formula. Although chlorine as an element is a diatomic molecule, Cl2, elemental chlorine is not part of this ionic compound. The chlorine is in the form of a negatively charged ion, not the neutral element. The 2 subscript is in the ionic formula because we need two Cl− ions to balance the charge on one Mg2+ ion.

Example (PageIndex{2}):

Write the proper ionic formula for each of the two given ions.

- Ca2+ and Cl−

- Al3+ and F−

- Al3+ and O2−

Solution

- We need two Cl− ions to balance the charge on one Ca2+ ion, so the proper ionic formula is CaCl2.

- We need three F− ions to balance the charge on the Al3+ ion, so the proper ionic formula is AlF3.

- With Al3+ and O2−, note that neither charge is a perfect multiple of the other. This means we have to go to a least common multiple, which in this case will be six. To get a total of 6+, we need two Al3+ ions; to get 6−, we need three O2− ions. Hence the proper ionic formula is Al2O3.

Exercise (PageIndex{2})

Write the proper ionic formulas for each of the two given ions.

- Fe2+ and S2−

- Fe3+ and S2−

Answers

- FeS

- Fe2S3

Naming Ionic Compounds

Fe Cation Charge Definition

Naming ionic compounds is simple: combine the name of the cation and the name of the anion, in both cases omitting the word ion. Do not use numerical prefixes if there is more than one ion necessary to balance the charges. NaCl is sodium chloride, a combination of the name of the cation (sodium) and the anion (chloride). MgO is magnesium oxide. MgCl2 is magnesium chloride—not magnesium dichloride.

In naming ionic compounds whose cations can have more than one possible charge, we must also include the charge, in parentheses and in roman numerals, as part of the name. Hence FeS is iron(II) sulfide, while Fe2S3 is iron(III) sulfide. Again, no numerical prefixes appear in the name. The number of ions in the formula is dictated by the need to balance the positive and negative charges.

Example (PageIndex{3}):

Name each ionic compound.

- CaCl2

- AlF3

- Co2O3

Solution

- Using the names of the ions, this ionic compound is named calcium chloride. It is not calcium(II) chloride because calcium forms only one cation when it forms an ion, and it has a characteristic charge of 2+.

- The name of this ionic compound is aluminum fluoride.

- We know that cobalt can have more than one possible charge; we just need to determine what it is. Oxide always has a 2− charge, so with three oxide ions, we have a total negative charge of 6−. This means that the two cobalt ions have to contribute 6+, which for two cobalt ions means that each one is 3+. Therefore, the proper name for this ionic compound is cobalt(III) oxide.

Exercise (PageIndex{3})

Name each ionic compound.

- Sc2O3

- AgCl

How do you know whether a formula—and by extension, a name—is for a molecular compound or for an ionic compound? Molecular compounds form between nonmetals and nonmetals, while ionic compounds form between metals and nonmetals. The periodic table can be used to determine which elements are metals and nonmetals.

There also exists a group of ions that contain more than one atom. These are called polyatomic ions. Table (PageIndex{2}) lists the formulas, charges, and names of some common polyatomic ions. Only one of them, the ammonium ion, is a cation; the rest are anions. Most of them also contain oxygen atoms, so sometimes they are referred to as oxyanions. Some of them, such as nitrate and nitrite, and sulfate and sulfite, have very similar formulas and names, so care must be taken to get the formulas and names correct. Note that the -ite polyatomic ion has one less oxygen atom in its formula than the -ate ion but with the same ionic charge.

| Name | Formula and Charge |

|---|---|

| ammonium | NH4+ |

| acetate | C2H3O2−, or CH3COO− |

| bicarbonate (hydrogen carbonate) | HCO3− |

| bisulfate (hydrogen sulfate) | HSO4− |

| carbonate | CO32− |

| chlorate | ClO3− |

| chromate | CrO42− |

| cyanide | CN− |

| dichromate | Cr2O72− |

| Name | Formula and Charge |

|---|---|

| hydroxide | OH− |

| nitrate | NO3− |

| nitrite | NO2− |

| peroxide | O22− |

| perchlorate | ClO4− |

| phosphate | PO43− |

| sulfate | SO42− |

| sulfite | SO32− |

| triiodide | I3− |

The naming of ionic compounds that contain polyatomic ions follows the same rules as the naming for other ionic compounds: simply combine the name of the cation and the name of the anion. Do not use numerical prefixes in the name if there is more than one polyatomic ion; the only exception to this is if the name of the ion itself contains a numerical prefix, such as dichromate or triiodide.

Writing the formulas of ionic compounds has one important difference. If more than one polyatomic ion is needed to balance the overall charge in the formula, enclose the formula of the polyatomic ion in parentheses and write the proper numerical subscript to the right and outside the parentheses. Thus, the formula between calcium ions, Ca2+, and nitrate ions, NO3−, is properly written Ca(NO3)2, not CaNO32 or CaN2O6. Use parentheses where required. The name of this ionic compound is simply calcium nitrate.

Example (PageIndex{4}):

Write the proper formula and give the proper name for each ionic compound formed between the two listed ions.

- NH4+ and S2−

- Al3+ and PO43−

- Fe2+ and PO43−

Solution

- Because the ammonium ion has a 1+ charge and the sulfide ion has a 2− charge, we need two ammonium ions to balance the charge on a single sulfide ion. Enclosing the formula for the ammonium ion in parentheses, we have (NH4)2S. The compound’s name is ammonium sulfide.

- Because the ions have the same magnitude of charge, we need only one of each to balance the charges. The formula is AlPO4, and the name of the compound is aluminum phosphate.

- Neither charge is an exact multiple of the other, so we have to go to the least common multiple of 6. To get 6+, we need three iron(II) ions, and to get 6−, we need two phosphate ions. The proper formula is Fe3(PO4)2, and the compound’s name is iron(II) phosphate.

Exercise (PageIndex{4})

Write the proper formula and give the proper name for each ionic compound formed between the two listed ions.

- NH4+ and PO43−

- Co3+ and NO2−

Answers

- (NH4)3PO4, ammonium phosphate

- Co(NO2)3, cobalt(III) nitrite

Food and Drink App: Sodium in Your Food

Charges Of Elements List

The element sodium, at least in its ionic form as Na+, is a necessary nutrient for humans to live. In fact, the human body is approximately 0.15% sodium, with the average person having one-twentieth to one-tenth of a kilogram in their body at any given time, mostly in fluids outside cells and in other bodily fluids.

Sodium is also present in our diet. The common table salt we use on our foods is an ionic sodium compound. Many processed foods also contain significant amounts of sodium added to them as a variety of ionic compounds. Why are sodium compounds used so much? Usually sodium compounds are inexpensive, but, more importantly, most ionic sodium compounds dissolve easily. This allows processed food manufacturers to add sodium-containing substances to food mixtures and know that the compound will dissolve and distribute evenly throughout the food. Simple ionic compounds such as sodium nitrite (NaNO2) are added to cured meats, such as bacon and deli-style meats, while a compound called sodium benzoate is added to many packaged foods as a preservative. Table (PageIndex{3}) is a partial list of some sodium additives used in food. Some of them you may recognize after reading this chapter. Others you may not recognize, but they are all ionic sodium compounds with some negatively charged ion also present.

| Sodium Compound | Use in Food |

|---|---|

| Sodium acetate | preservative, acidity regulator |

| Sodium adipate | food acid |

| Sodium alginate | thickener, vegetable gum, stabilizer, gelling agent, emulsifier |

| Sodium aluminum phosphate | acidity regulator, emulsifier |

| Sodium aluminosilicate | anticaking agent |

| Sodium ascorbate | antioxidant |

| Sodium benzoate | preservative |

| Sodium bicarbonate | mineral salt |

| Sodium bisulfite | preservative, antioxidant |

| Sodium carbonate | mineral salt |

| Sodium carboxymethylcellulose | emulsifier |

| Sodium citrates | food acid |

| Sodium dehydroacetate | preservative |

| Sodium erythorbate | antioxidant |

| Sodium erythorbin | antioxidant |

| Sodium ethyl para-hydroxybenzoate | preservative |

| Sodium ferrocyanide | anticaking agent |

| Sodium formate | preservative |

| Sodium fumarate | food acid |

| Sodium gluconate | stabilizer |

| Sodium hydrogen acetate | preservative, acidity regulator |

| Sodium hydroxide | mineral salt |

| Sodium lactate | food acid |

| Sodium malate | food acid |

| Sodium metabisulfite | preservative, antioxidant, bleaching agent |

| Sodium methyl para-hydroxybenzoate | preservative |

| Sodium nitrate | preservative, color fixative |

| Sodium nitrite | preservative, color fixative |

| Sodium orthophenyl phenol | preservative |

| Sodium propionate | preservative |

| Sodium propyl para-hydroxybenzoate | preservative |

| Sodium sorbate | preservative |

| Sodium stearoyl lactylate | emulsifier |

| Sodium succinates | acidity regulator, flavor enhancer |

| Sodium salts of fatty acids | emulsifier, stabilizer, anticaking agent |

| Sodium sulfite | mineral salt, preservative, antioxidant |

| Sodium sulfite | preservative, antioxidant |

| Sodium tartrate | food acid |

| Sodium tetraborate | preservative |

The use of so many sodium compounds in prepared and processed foods has alarmed some physicians and nutritionists. They argue that the average person consumes too much sodium from his or her diet. The average person needs only about 500 mg of sodium every day; most people consume more than this—up to 10 times as much. Some studies have implicated increased sodium intake with high blood pressure; newer studies suggest that the link is questionable. However, there has been a push to reduce the amount of sodium most people ingest every day: avoid processed and manufactured foods, read labels on packaged foods (which include an indication of the sodium content), don’t oversalt foods, and use other herbs and spices besides salt in cooking.

Figure (PageIndex{2}): Food labels include the amount of sodium per serving. This particular label shows that there are 75 mg of sodium in one serving of this particular food item.

Key Takeaways

- Ions form when atoms lose or gain electrons.

- Ionic compounds have positive ions and negative ions.

- Ionic formulas balance the total positive and negative charges.

- Ionic compounds have a simple system of naming.

- Groups of atoms can have an overall charge and make ionic compounds.